Professor Steve Keen, Distinguished Research Fellow, Institute for Strategy, Resilience and Security, University College London.

One of the great ironies of economics is that, while the public regards economists as experts on money, the issue of how money is created is still not settled within economics.

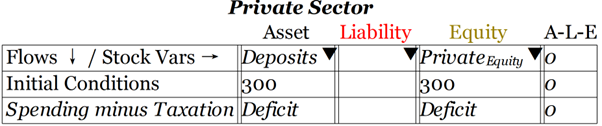

In 2014, the Bank of England published a landmark paper explicitly rejecting the textbook model of money creation, stating that:

Money creation in practice differs from some popular misconceptions—banks do not act simply as intermediaries, lending out deposits that savers place with them, and nor do they ‘multiply up’ central bank money to create new loans and deposits…

The reality of how money is created today differs from the description found in some economics textbooks:

- Rather than banks receiving deposits when households save and then lending them out, bank lending creates deposits.

- In normal times, the central bank does not fix the amount of money in circulation, nor is central bank ‘multiplied up’ into more loans and deposits. (McLeay, Radia, and Thomas 2014, p. 14)

Several other Central Banks published related papers, notably the Bundesbank in 2017, which stated that:

It suffices to look at the creation of (book) money as a set of straightforward accounting entries to grasp that money and credit are created as the result of complex interactions between banks, non- banks and the central bank. And a bank’s ability to grant loans and create money has nothing to do with whether it already has excess reserves or deposits at its disposal (Deutsche Bundesbank 2017, p. 17)

And yet, just five years later, the Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to Bernanke, Diamond and Dybvig for work which, as the “Scientific Background” to the Prize noted, claimed that banks function as “financial intermediaries” which “channel funds from savers to investors, receiving funds from some customers and using the funds to finance others” (Committee for the Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2022, p. 4). The document did not cite these Central Bank papers, let alone note the contrary arguments in them.

In this paper, I use double-entry bookkeeping to prove that mainstream economists are wrong about banks and their importance in macroeconomics. Banks are money creators, not “financial intermediaries”, and financial flow analysis shows that bank credit creation has significant macroeconomic effects, contrary to assertions by Bernanke (Bernanke 2000, p. 24) and the Committee for the Nobel Prize in Economics.

Double-Entry Bookkeeping and the invalidity of mainstream economics

Banks are creatures of accounting: they create not goods and services, but financial assets and liabilities. Double-entry bookkeeping is central to both accounting and the operation of actual banks. Yet one striking feature of mainstream economics is the near complete absence of double-entry bookkeeping in its models of banking and money creation. This leads to mainstream economics being replete with concepts and models that contradict double-entry bookkeeping—and which are therefore false as models of the real-world.

The two essentials of double-entry bookkeeping are the classification of all accounts as either Assets or Liabilities—with the gap between the two being the Equity of the entity in question—and the recording of all transactions twice, so that the rule that is maintained for every transaction.

I have developed an Open-Source (i.e., free) software program called Minsky to enable monetary dynamics to be modelled easily (Minsky can be downloaded from the software repository SourceForge at https://sourceforge.net/projects/minsky/). Its key feature is called a Godley Table (named in honour of the non-mainstream economist Wynne Godley). A Godley Table classifies all financial accounts as either Assets or Liabilities, checks that every transaction obeys the rule that , and allows the user to build dynamic, monetary models of the economy that way.

When Neoclassical ideas about money are put into Minsky, they are shown to either contradict the rules of double entry bookkeeping, or to not have the outcome that Neoclassical economists expect. Take, for example, Bernanke and Blinder’s IS/LM-style model of banking (Bernanke and Blinder 1988). in which:

“the supply of deposits (we ignore cash) is equal to bank reserves, R, times the money multiplier” (Bernanke and Blinder 1988, p. 436).

This is standard fare in mainstream economics, and it presumes a simple mechanism between Reserves and the creation of Deposits. But it is easily shown that this mechanism either (1) violates the principles of double-entry bookkeeping, or (2) depends upon the existence of cash, which they ignore.

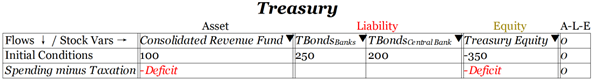

Before I illustrate this, I will show why the Bundesbank’s comments that “the creation of (book) money” is “as a set of straightforward accounting entries”, and that “a bank’s ability to grant loans and create money has nothing to do with whether it already has excess reserves” are accurate—unlike mainstream economics. To create a loan, a bank simply adds the same number to its outstanding loans as it does to its Deposits: “Loans create Deposits”. The bank customer gets more money in their account, matched by an identical debt to the bank. Bank Assets—in the form of loans—rise as much as Liabilities—in the form of Deposits—and the key accounting equation is satisfied.

Reserves play no role whatsoever in this process—see Figure 1, which shows Credit dollars being added to the Banks’ Liabilities of Deposits, and Credit dollars also added to Banks’ Assets of Loans. It is, as the Bundesbank says, an extremely straightforward and easy to understand process.

Figure 1: The absolute basics of real-world lending: Loans create Deposits

Mainstream economists—including members of the Federal Reserve’s “Federal Open Market Committee” (FOMC) who determine monetary policy, and set interest rates—also believe that their model of banks lending from Reserves is quite simple and straightforward, as these quotes from Ben Bernanke and Charles Plosser (then President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia) in 2009—during the depths of the 2008 financial crisis—illustrate:

Large increases in bank reserves brought about through central bank loans or purchases of securities are a characteristic feature of the unconventional policy approach known as quantitative easing. The idea behind quantitative easing is to provide banks with substantial excess liquidity in the hope that they will choose to use some part of that liquidity to make loans or buy other assets. (Bernanke 2009, p. 5)

As real rates rise, the opportunity cost of banks holding on to vast excess reserves may lead to a rapid increase in the money multiplier and a conversion of excess reserves into loans or borrowed money. (FOMC 2009, p. 55)

In fact, the “conversion of excess reserves into loans” is virtually impossible: certainly, the simple, direct relationship between Loans and Deposits is does not exist. “Lending from Reserves” means that Reserves go down. Adding money to Deposits means that Deposits go up. Not only does this combination violate the rule that (as Figure 2 shows), it also doesn’t convert Reserves into Loans. Therefore, an attempt to fit the mainstream economic idea that banks lend out Reserves leads to the absurdity that lending reduces bank assets, rather than increasing them, breaks the laws of accounting, and shows Banks giving away Credit for free.

Figure 2: “Lend from Reserves” violates the rules of accounting

To conform to the laws of accounting, “Lending from Reserves” would have to reduce Reserves and increase Loans, as shown in Figure 3. The accounting is now valid, but there is still one weakness: how do borrowers get the money they have borrowed?

Figure 3: “Lend from Reserves” now obeys the rules of accounting–but how do borrowers get the money?

The only way this can make sense is if the loan is in the form of cash, as shown in Figure 4—but recall that, in their model of lending, Bernanke and Blinder ignored cash.

Figure 4: “Lend from Reserves” requires that loans are in the form of cash

Of course, banks generally do not make loans in cash today—instead, they directly add Credit to Deposit accounts, as shown in Figure 1. Reserves play no role in lending, as the Bundesbank stated, and the mainstream attempt to argue that they do generates a caricature of actual bank practice.

The same applies to another aspect of mainstream thinking about banks, that they are “mere intermediaries” that enable savers to lend to borrowers.

Loanable Funds versus Bank Originated Money and Debt

Though Paul Krugman is the main proponent of the “Loanable Funds” model of banking, Bernanke also confirmed that he accepted it when he described it as compatible with the model in (Bernanke and Blinder 1988):

The theory of the bank-lending channel holds that monetary policy works in part by affecting the supply of loans offered by depository institutions. This concept is a cousin of the idea I proposed in my paper on the Great Depression, that the failures of banks during the 1930s destroyed “information capital” and thus reduced the effective supply of credit to borrowers. Alan Blinder and I adapted this general idea to show how, by affecting banks’ loanable funds, monetary policy could influence the supply of intermediated credit (Bernanke and Blinder, 1988).

Loanable Funds sees banks, not as issuers of debt, but as intermediaries that collect funds from savers and lend them out to borrowers. Mainstream economists do not consider that this means (a) that savers, and not banks, would be the actual owners of the debt issued, and (b) that bank deposits could not be demand deposits in this model. Instead, they simply assume that loans redistribute spending power from savers to borrowers, and that repayment of loans does the opposite, as the following quote from Bernanke illustrates in the case of the Great Depression:

The idea of debt-deflation goes back to Irving Fisher … Fisher’s idea was less influential in academic circles, though, because of the counterargument that debt-deflation represented no more than a redistribution from one group (debtors) to another (creditors). Absent implausibly large differences in marginal spending propensities among the groups, it was suggested, pure redistributions should have no significant macroeconomic effects. (Bernanke 2000, p. 24. Emphasis added)

The italicized text indicates that Bernanke assumes that a loan causes the spending power of savers (creditors in his language) to fall and that of borrowers (debtors) to rise, while repayment does the opposite. Therefore, in the Loanable Funds model, aggregate spending only varies with changes in the level of debt if Borrowers spend more rapidly than Savers.

Figure 5 sets this model out in Minsky: Savers lend Credit dollars per year to Borrowers (this is negative when debt is repaid); Borrowers pay Interest dollars per year to Savers; Savers pay a Fee to the banks for arranging the loans; Savers spend on Borrowers; Borrowers spend on Savers; and the Banks spend on both Savers and Borrowers.

Figure 5: A simple model of Loanable Funds–but where is the Loan itself?

Even at this point, there is an obvious problem with this model: where is the debt itself? It doesn’t appear here because, in Loanable Funds, the debt (Loans) is an asset of the Savers. To show it, we need to add another table for the Savers: one table is not enough.

Before I add that table, I want to show what the real-world situation, in which banks issue loans, looks like. In this case, Banks lend to Borrowers, Borrowers pay interest to the Banks, and there is no Fee charged on Savers. As Figure 6 shows, Loans do appear in this model, because they are Assets of the Banks: there is no need for an additional table to show them, This illustrates that the real-world practice of banking—which I call “Bank Originated Money and Debt” (BOMD)—is actually simpler than the model of Loanable Funds.

Figure 6: The real-world situation of Banks lending to Borrowers

That said, Figure 7 shows the minimum system needed to model Loanable Funds, since Loans now appear as Assets of the Savers.

Figure 7: Two Godley Tables–one for Banks, the other for Savers, are needed to model Loanable Funds

If this model described reality, then Bernanke would be right that “pure redistributions”—by which he means net lending, which I call Credit here—would “no significant macroeconomic effects” unless there were “implausibly large differences in marginal spending propensities among the groups”. In Figure 8, I build such a model, with Borrowers spending their bank balances 4 times per year, Savers spending 2 times per year, and Banks only 0.1 times per year. I then run it with varying levels of credit: initially 0% of GDP, then 5% so that debt grows, the minus 5% so that it falls, and finally back to zero percent again. There are changes in GDP, but they precisely match changes in the velocity of money.

Figure 8: Loanable Funds with large differences in spending propensities

These are however second-order effects, since there is no change in the amount of money in the economy, and therefore GDP can only grow or fall as much as the velocity of money increases or decreases. In that sense, there’s no great harm done to macroeconomics if banks, and debt, and indeed money are ignored in macroeconomic models—which is the case with Neoclassical macroeconomics.

However, what happens if we model the real-world situation that banks are not intermediaries between Savers and Borrowers, but creators of both debt and money? That is shown in Figure 9, which was created from the model in Figure 8 simply by showing Loans as an Asset of the Banks, rather than Savers, directing Interest payments to the Banks rather than Savers, and deleting the now superfluous Fee.

Figure 9: The real-world of bank originated money and debt

The result is dramatically different, because positive Credit now creates new money, which increases GDP. Similarly, negative Credit destroys money and reduces GDP.

Obviously, from the simulations above, Credit significantly affects macroeconomics in the real-world of Bank Originated Money and Debt (BOMD), but it does not in the Neoclassical fictional world of Loanable Funds.

The Logic of Credit

To understand what lies behind those simulations, I use a device that I call a “Moore Table” (in honour of the great non-mainstream economist Basil Moore) to show that, in the real-world, Credit is part of both Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Income. I abandon the frankly silly Neoclassical categories of “Savers” and “Borrowers”, and consider instead an economy consisting of Households, a Services sector, and a Manufacturing sector, where each sector spends a certain number of dollars per year on the other.

In the first Moore Table shown in Table 1, I omit lending completely, and consider just expenditure financed out of existing money. Households spend A dollars per year on Services and B dollars per year on manufacturing; Services spend C dollars per year on Households, and D dollars per year on Manufacturing; and Manufacturing spends E dollars per year on Households and F dollars per year on Services. The diagonal entries show expenditure; the off-diagonal elements show income, and in the fundamental relation in macroeconomics, aggregate income, which is the negative of the sum of the diagonal elements, is identical to aggregate expenditure, which is the positive sum of the off-diagonal elements.

Table 1: A Moore Table showing expenditure IS income for a 3-sector economy

|

|

Households

|

Services

|

Manufacturing

|

Sum

|

|

Households

|

-A-B

|

A

|

B

|

0

|

|

Services

|

C

|

-C-D

|

D

|

0

|

|

Manufacturing

|

E

|

F

|

-E-F

|

0

|

|

Sum

|

(C+E)-(A+B)

|

(A+F)-(C+D)

|

(B+D)-(E+F)

|

0

|

This leads to Equation 1:

In Table 2, I show the Loanable Funds by imagining that the Services sector lends Credit dollars per year to the Households sector, and then Households use this borrowed money to buy more goods from Manufacturing. However, the lending by Services lending comes at the expense of the Service Sector’s spending on Manufacturing (you can’t spend money you’ve lent to someone else). So Services spends (D-Credit) dollar per year on Manufacturing, whereas Households spend (B+Credit) dollars per year on Manufacturing. Lending from the Services Sector to the Household Sector is neither Expenditure nor Income, so the transfer of money can’t be shown horizontally: it is instead shown as a transfer across the diagonal, reducing the expenditure of the lender (Services) and increasing the spending of the borrower (Households). Households pay Interest dollars per year on their outstanding debt to Services, and since this is both an expenditure and an income, it is shown horizontally.

Table 2: The Moore Table for Loanable Funds

|

|

Households

|

Services

|

Manufacturing

|

Sum

|

|

Households

|

-(A+B+Credit +Interest)

|

A+Interest

|

B+Credit

|

0

|

|

Services

|

C

|

-(C+D-Credit)

|

D-Credit

|

0

|

|

Manufacturing

|

E

|

F

|

-(E+F)

|

0

|

|

Sum

|

(C+E) – (A + B + Credit + Interest)

|

(A+ F+ Interest) – (C+D-Credit)

|

(B+Credit) + (D-Credit) – (E+F)

|

0

|

When you add up expenditure and income in this table, Credit cancels out: for every positive entry for Credit in either Aggregate Demand (the negative of the sum of the diagonal cells) or Aggregate Income (the sum of the off-diagonal cells), there’s an offsetting negative entry that cancels it out. The only effect of lending on this model of the economy is that Interest payments turn up as part of both expenditure and income:

Table 3 shows the real-world situation of “Bank Originated Money and Debt”. It’s more complicated than the other tables, because we have to add the Banking Sector to the model, and we have to include the Banking Sector’s Assets—where Credit appears as an increase in the Banking Sector’s loans to the Household Sector—as well as its Liabilities and its Equity. I also add spending by the Banking sector on the other 3 sectors. Table 3 explicitly shows all spending as passing through the Liabilities (Deposit accounts) and Equity sides of the banking sector’s accounts. The Household Sector’s expenditure on Manufacturing includes Credit, as in Loanable Funds, but this credit-financed spending does not come at the expense of any other sector’s expenditure: instead, it comes from the creation of new money via the expansion of the Banking Sector’s Liabilities and Assets.

Table 3: The Moore Table for Bank Originated Money and Debt

|

|

Assets

|

Liabilities (Deposit Accounts)

|

Equity

|

|

|

|

Debt

|

Households

|

Services

|

Manufacturing

|

Bank

|

Sum

|

|

Households

|

Credit

|

-(A+B + Credit + Interest)

|

A

|

B + Credit

|

Interest

|

0

|

|

Services

|

|

C

|

-(C+D)

|

D

|

|

0

|

|

Manufacturing

|

|

E

|

F

|

-(E+F)

|

|

0

|

|

Bank

|

|

G

|

H

|

I

|

-(G+H+I)

|

|

|

Sum

|

|

(C+E+G) – (A+B + Credit + Interest)

|

(A+F+H)-(C+D)

|

(B+D+I+Credit)-(E+F)

|

Interest-(G+H+I)

|

0

|

The key outcome is that Credit does not cancel out, as it does in Loanable Funds: there is a single entry for Credit in Aggregate Expenditure—it finances part of the Household Sector’s purchases from the Manufacturing Sector—and a single entry in Aggregate Income—where it is part of the Manufacturing Sector’s income:

Consequently, in the model shown in Table 3—and in the real world—credit is a substantial source of both Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Income. This is the logical explanation of the difference in behavior between the “Loanable Funds” model shown in Figure 8 and the BOMD model shown in Figure 9. It is also the explanation for the real-world phenomena of debt-deflationary crises like the Great Recession, the Great Depression, and the Panic of 1837. Neoclassical economics, by ignoring banks, debt and money in its macroeconomic models, is ignoring the main factors that drive economic performance, and also cause economic crises.

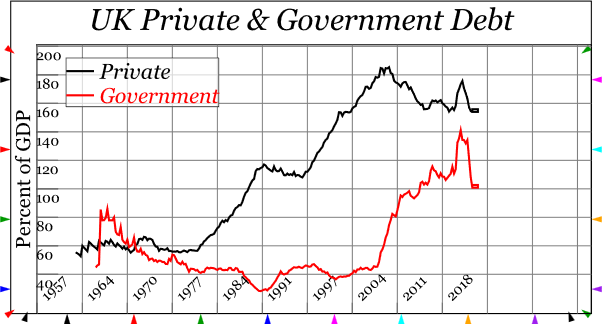

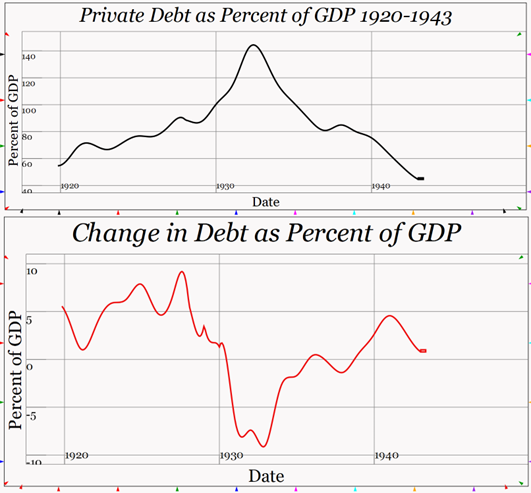

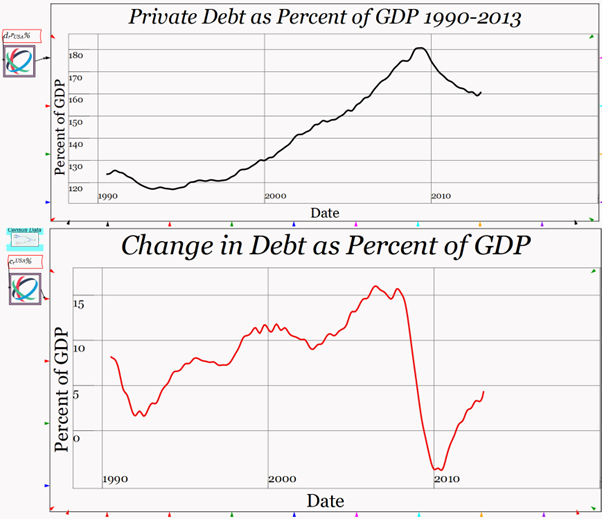

This is apparent when, using the guidance above, we look at the role of both private debt and credit in the Great Recession.

The Empirics of Credit

Far from Credit having “no significant macroeconomic effects”, as Bernanke asserted, in the real-world Credit is overwhelmingly the factor causing economic fluctuations—and especially severe downturns like the Great Recession. This is because it is by far the most volatile component of aggregate demand—which mainstream Neoclassical economists miss because their false Loanable Funds theory tells them not to even look at data like that plotted in Figure 10.

Figure 10: Private Debt, Credit and Unemployment in the USA 1970-2012

In doing so, they are like the Ptolemaic astronomers that Galileo ridiculed in correspondence with Kelper five centuries ago, for their steadfast refusal to look through Galileo’s telescope. They therefore never saw the moons of Jupiter, whose existence demolished their Earth-centric vision of the Universe:

What is to be done? Shall we side with Democritus or Heraclitus? I think, my Kepler, we will laugh at the extraordinary stupidity of the multitude. What do you say to the leading philosophers of the faculty here, to whom I have offered a thousand times of my own accord to show my studies, but who with the lazy obstinacy of a serpent who has eaten his fill have never consented to look at planets, nor moon, nor telescope? Verily, just as serpents close their ears, so do these men close their eyes to the light of truth. (Gebler 1879, p. 26)

References

- Bernanke, Ben. 2009. “The Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet: An Update.” In Federal Reserve Board Conference on Key Developments in Monetary Policy. Washington, DC: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

- Bernanke, Ben S. 2000. Essays on the Great Depression (Princeton University Press: Princeton).

- Bernanke, Ben S., and Alan S. Blinder. 1988. ‘Credit, Money, and Aggregate Demand’, American Economic Review, 78: 435-39.

- Bholat, David, and Robin Darbyshire. 2016. “Accounting in central banks.” In, edited by Bank of England. London.

- Carney, John. 2013. “Basics of Banking: Loans Create a Lot More Than Deposits.” In NetNet, edited by John Carney, Brilliant simple example of loan/deposit creation followed by regulatory requirements. Well worth modeling in Minsky. New York: CNBC.

- Committee for the Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, The. 2022. “Financial Intermediation and the Economy.” In. Stockholm: The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

- Deutsche Bundesbank. 2017. ‘The role of banks, non- banks and the central bank in the money creation process’, Deutsche Bundesbank Monthly Report, April 2017: 13-33.

- FOMC. 2009. “Meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee on December 15–16, 2009.” In.: Federal Reserve.

- Gebler, Karl von. 1879. “Galileo Galilei and the Roman Curia.” In. London: C. Kegan Paul & Co.

- McLeay, Michael, Amar Radia, and Ryland Thomas. 2014. ‘Money creation in the modern economy’, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, 2014 Q1: 14-27.