Many people seem offended by the very idea that banks can create money “out of nothing”, or that governments can finance their spending by creating money, rather than borrowing. They seem wedded to the idea that money must be a physical thing, and therefore it can’t be created “out of nothing”.

This probably arises from the myth of barter that economics has been infected with ever since Adam Smith’s declaration that barter was an innate characteristic of humans:

THIS division of labour, from which so many advantages are derived, is the … consequence of … the propensity to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another… Nobody ever saw a dog make a fair and deliberate exchange of one bone for another with another dog. (Smith 1776)

Barter involves two parties with physical things to exchange—a flower seller has flowers, a carpenter has chairs. There are two parties, two commodities, and the exchange takes place when both parties are satisfied with the exchange ratio of flowers to chairs. Barter is thus a two party, two commodity thing.

Banking, people seem to think, replaced an imagined (but not real) past in which we literally did exchange one physical thing for another—flowers for chairs—with a present in which we transfer funds electronically between bank accounts, but there is still a physical thing, like gold, backing today’s electronic money.

There isn’t, because money is not a physical thing: it’s a social thing, an “IOU”, which everyone in a society accepts in payment. It is a third party’s “promise to pay” that a buyer transfers to a seller, and the seller accepts this third party’s promise as complete payment for whatever physical object or service the seller transfers to the buyer. That third party is a bank.

The great Italian monetary theorist Augusto Graziani put it this way—in a paper written in 1989 when cheques (or cash), rather than transfers between bank accounts, were the main ways that bank payments were made:

When an agent makes a payment by means of a cheque, he satisfies his partner by the promise of the bank to pay the amount due. Once the payment is made, no debt and credit relationships are left between the two agents. But one of them is now a creditor of the bank, while the second is a debtor of the same bank… any monetary payment must therefore be a triangular transaction, involving at least three agents, the payer, the payee, and the bank. (Graziani 1989)

Graziani’s insight inspired me to design Minsky, an Open Source (i.e., free) system dynamics program which uses double-entry bookkeeping to model financial flows (click on the link to download a copy). In this post, I’ll show how Minsky can prove that both banks and governments can create “Money from Nothing”. Banks create money when new loans exceed loan repayments; Governments create money when their spending exceeds taxation. Though in practice, they start from non-zero—there are existing loans, existing deposits, existing government bonds, etc.—the mathematics of the systems by which they create money mean that they can start from zero and still create money.

This explains how government (“Fiat”) and bank (“Credit”) money are both effectively “endogenous”. The word “endogenous” used to be thrown around a lot in monetary debates, to distinguish the Post Keynesian view that banks controlled the money supply (Moore 1979; Jarsulic 1989; Wray 1989; Wray 1990; Lavoie 1995; Palley 2002; Godley 2004; Wray 2007; Fullwiler 2013; Wheat 2017; Lavoie and Reissl 2019) from the Neoclassical view that banks needed to be “seeded” by the creation of Reserves by the government (Kinsella 2010; Deleidi and Fontana 2019; Axilrod and Lindsey 1981; de Soto 1995; O’Brien 2007; Keister and McAndrews 2009; Martin, McAndrews, and Skeie 2013), before they could create more money themselves by lending. The practice developed—at least amongst Post Keynesian economists—or referring to private bank money creation as endogenous, and government money creation as exogenous.

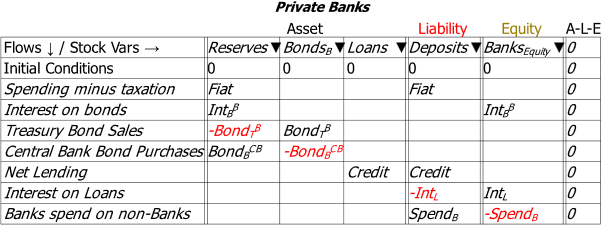

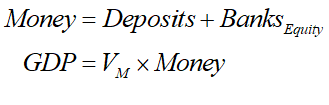

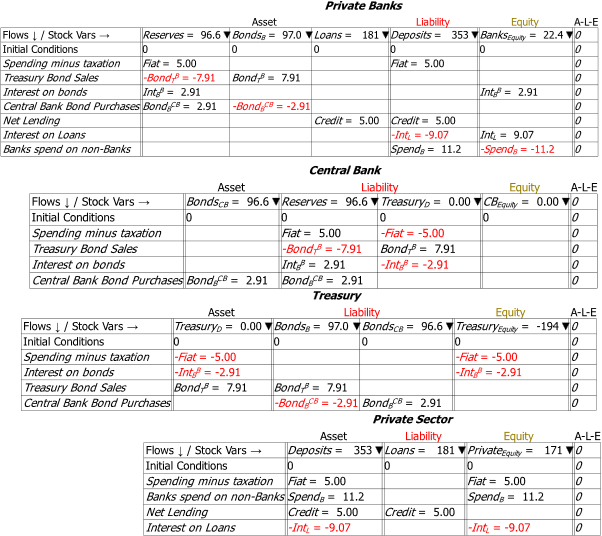

However, in a strictly mathematical sense, both Fiat and Credit money are endogenous, in that they can both start from zero and create money. The Minsky model in this post proves this, working from an extremely simplified aggregate model of banking. Figure 1 shows the basic operations of Fiat and Credit money. Working down its seven rows, the first four rows show the basic operations of Fiat money creation, while the last three show the basics of Credit money creation:

- The excess of government spending over taxation “Fiat” (this is positive when spending exceeds taxation and normally called a “Deficit”, and negative when taxation exceeds spending and normally called a “Surplus”) is added to private sector bank accounts (“Deposits“) and also bank settlement accounts (“Reserves“);

- The Treasury pays interest to banks on existing bonds (“IntBB“);

- Treasury sells bonds of equivalent value to the “deficit”—which I call Fiat here—and interest on existing bonds owned by banks (“BondsB“);

- The Central Bank buys bonds from private banks (“BondsBCB“);

- Private banks net lending (which can be positive or negative) adds Credit dollars per year to Deposits and also to Loans;

- The non-bank private sector pays IntL dollars per year on existing debt, which is credited to the Banking sector’s short-term equity BanksEquity; and

- Banks spend SpendB dollars per year buying goods and services from the private non-bank sector.

Figure 1: The basic operations in Fiat and Credit money

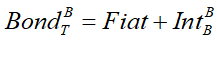

Most countries have laws that require the Treasury to not run an overdraft at the Central Bank. In practice this means that the Treasury issues bonds equivalent to the excess of spending over taxation (“Fiat” here), plus interest on outstanding bonds. I model this here by the relationship that:

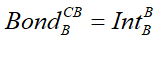

Secondly, Central Banks buy and sell bonds in trade with private banks in what are called Open Market Operations (OM)). This model captures the aggregate of this buying and selling over a year, and for convenience I assume that the net buying of bonds by the Central Bank equals the interest on existing bonds IntBB. This results in equation 1.2:

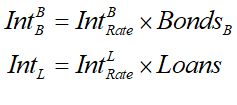

The interest rate that Treasury pays on bonds owned by the banks, and that the private sector pays on Loans, are introduced as parameters:

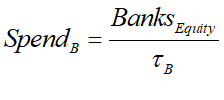

Bank spending on the non-bank private sector is modelled using the engineering concept of a “time constant”  , which indicates how many years that banks could spend without exhausting their equity:

, which indicates how many years that banks could spend without exhausting their equity:

Finally, GDP is modelled as the velocity of money times the money stock, which is defined here as Deposits plus BanksEquity:

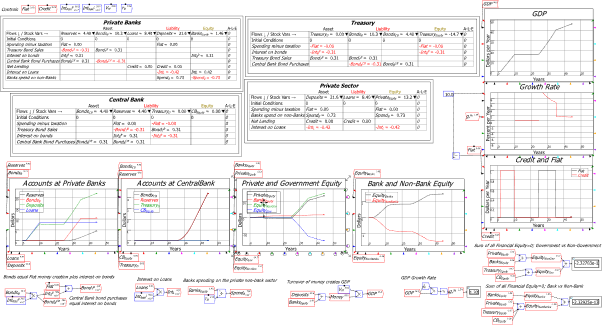

These equations are entered as flowcharts on the canvas—see Figure 2.

Figure 2: The flow equations in the model, as entered on Minsky’s canvas

Fiat and Credit are left undefined, so that they can be varied during a simulation.

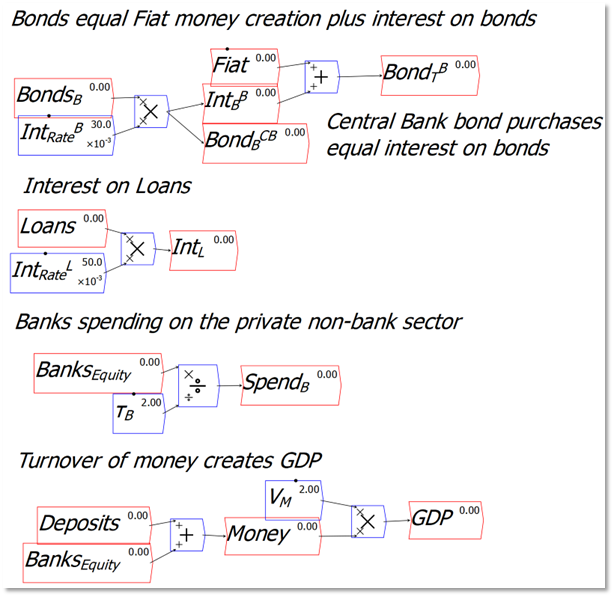

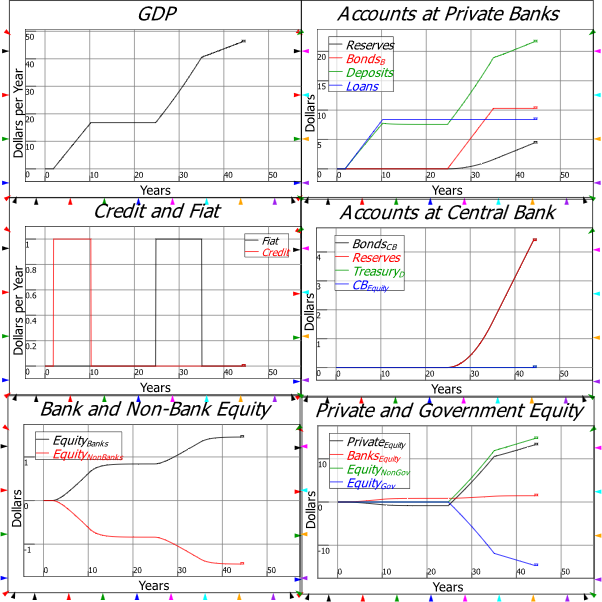

Figure 3 shows a run of the model in which Credit and Fiat were increased and decreased at different times. This both created and destroyed money, leading to varying rates of growth of GDP.

Figure 3: A simulation with varying levels of Fiat and Credit

The key result for this model is shown in Figure 4; though the model began with zero in every account, the flows generated positive sums for all accounts except TreasuryD, the Treasury’s account at the Central Bank—and this account remained non-negative, as required by law, since the expenditure out of the account was precisely matched by the monetary flows into in from bond sales.

Figure 4: The “Godley Tables” for the four sectors of the economy

Both credit money and fiat money creation are therefore “endogenous”: they don’t require any external input to enable money creation to commence. The decisions, by the government to spend more than it gets back in taxes, and by the banking system to create net new loans, not only create money but also ensure that the other accounts reach levels required by law. Banks, in particular, achieve positive equity—their Assets exceed their Liabilities—even though they began with zero equity in this simulation.

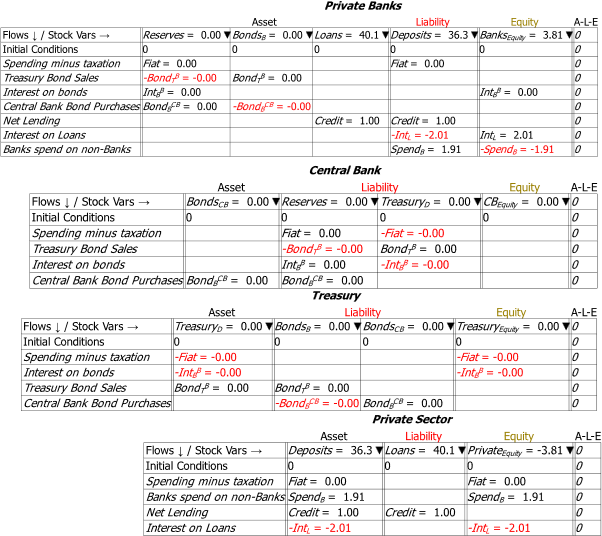

Figure 5 shows a simulation with only Credit money creation. Notice in this case that the positive equity for the banking sector is precisely equal to the negative equity for the non-bank private sector. This shows that in the absence of government money creation, the non-bank private sector must end up in negative net financial equity, since the banking sector must have positive (or more precisely, non-negative) financial equity.

Figure 5: Credit money creation only

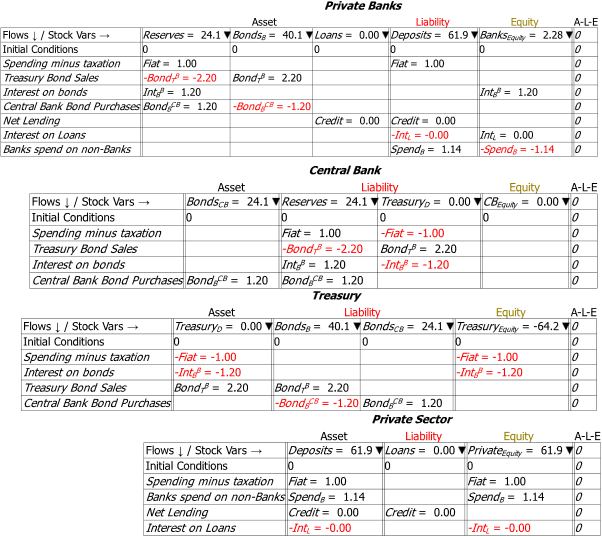

Figure 6 shows only Fiat money creation, and here the negative equity of the government sector—64.2 in this simulation—is precisely equal to the positive equity of the non-government sector—with 61.9 for the non-bank private sector and 2.3 for the banking sector.

Figure 6: Fiat money creation only

Therefore, neither the government nor the banks needs a stock of anything—gold, flowers, chairs, or anything else—before they create money. What they do need are people with whom they can have a financial relationship: taxpayers for the government, borrowers for the banks. Borrowers have to agree to go into debt; taxpayers simply have to be subjects of a given government, in which case they are recipients of government spending, and liable to pay taxation.

Libertarians might instinctively prefer private money creation (Credit) over government (Fiat), because the former involves free choice and the latter involves compulsion. But from a practical point of view, the “free choice” generates compulsion while the “compulsion” option generates freedom.

Credit money creation effectively forces the non-bank private sector into negative equity. Banks, by definition, have to have non-negative equity: if their assets exceed their liabilities, they are bankrupt. Bank lending generates positive equity for the banks, and it therefore necessarily generates negative equity for the non-bank private sector: if banks have financial assets that exceed their liabilities, then by the logic of double-entry bookkeeping, non-banks have identical negative financial equity.

This reality of private money creation is, I believe, a major reason why banks can entice us into speculation on the value of non-financial assets—things like houses and shares—which we buy with yet more borrowed money. We end up with asset bubbles and speculation dominating true enterprise.

On the other hand, though no-one enjoys paying taxes, if a government routinely spends more than it takes back in taxation, then the non-government sector gains positive financial equity—which is precisely equal in magnitude to the negative financial equity of the government sector. This effectively creates “free money” for the non-bank private sector, which allows it to undertake commerce on its own terms, without necessarily having to borrow from banks in the first instance.

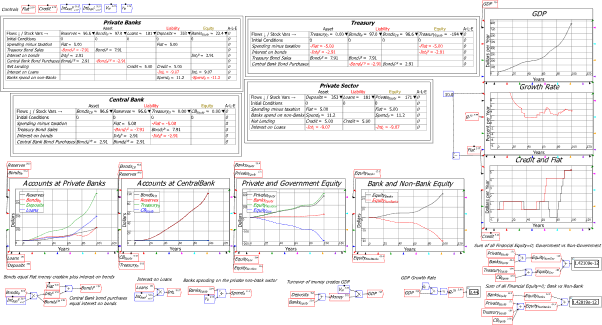

Figure 7 shows a “pulse” of Credit money creation, followed by a pulse of Fiat money creation. Though you’ll need to run the model yourself to see this clearly (I’ll post it on Patreon and link to it on Substack), when the credit money pulse stops, so does expansion of the economy. However when the fiat money pulse stops, growth continues because the interest paid on government bonds continues to create money.

Figure 7: Credit and Fiat money creation

If we could just get our heads around these practical realities of money creation, and throw the myths of Neoclassical and Austrian economists into the rubbish bin of history where they belong, then the monetary side of capitalism would function a damn sight better than it has under the last forty years of Neoliberalism.

Figure 8: The plots from the simulation in Figure 7

Axilrod, Stephen H., and David E. Lindsey. 1981. ‘Federal Reserve System Implementation of Monetary Policy: Analytical Foundations of the New Approach’, American Economic Review, 71: 246-52.

de Soto, Jesus Huerta. 1995. ‘A Critical Analysis of Central Banks and Fractional-Reserve Free Banking from the Austrian School Perspective’, Review of Austrian Economics, 8: 25-38.

Deleidi, Matteo, and Giuseppe Fontana. 2019. ‘Money Creation in the Eurozone: An Empirical Assessment of the Endogenous and the Exogenous Money Theories’, Review of Political Economy, 31: 559-81.

Fullwiler, Scott T. 2013. ‘An endogenous money perspective on the post-crisis monetary policy debate’, Review of Keynesian Economics, 1: 171–94.

Godley, Wynne. 2004. ‘Weaving Cloth from Graziani’s Thread: Endogenous Money in a Simple (but Complete) Keynesian Model.’ in Richard Arena and Neri Salvadori (eds.), Money, credit and the role of the state: Essays in honour of Augusto Graziani (Ashgate: Aldershot).

Graziani, Augusto. 1989. ‘The Theory of the Monetary Circuit’, Thames Papers in Political Economy, Spring: 1-26.

Jarsulic, M. 1989. ‘Endogenous credit and endogenous business cycles’, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 12: 35-48.

Keister, T., and J. McAndrews. 2009. “Why Are Banks Holding So Many Excess Reserves?” In. New York: Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Kinsella, Stephen. 2010. ‘Pedagogical Approaches to Theories of Endogenous versus Exogenous Money’, International Journal of Pluralism and Economics Education, 1: 276-82.

Lavoie, M. 1995. “Loanable Funds, Endogenous Money, and Minsky’s Financial Fragility Hypothesis.” In, 19 pages. University of Ottawa, Department of Economics, Working Papers.

Lavoie, Marc, and Severin Reissl. 2019. ‘Further insights on endogenous money and the liquidity preference theory of interest’, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 42: 503-26.

Martin, Antoine, James McAndrews, and David Skeie. 2013. “Bank Lending in Times of Large Bank Reserves.” In.: Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Moore, Basil J. 1979. ‘The Endogenous Money Supply’, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 2: 49-70.

O’Brien, Yueh-Yun June C. 2007. ‘Reserve Requirement Systems in OECD Countries’, SSRN eLibrary.

Palley, Thomas I. 2002. ‘Endogenous Money: What It Is and Why It Matters’, Metroeconomica, 53: 152-80.

Smith, Adam. 1776. An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (Liberty Fund: Indianapolis).

Wheat, David. 2017. ‘Teaching endogenous money with systems thinking and simulation tools’, Int. J. of Pluralism and Economics Education, 8.

Wray, L. Randall. 1990. Money and credit in capitalist economies: The endogenous money approach (Aldershot, U.K. and Brookfield, Vt.:

Elgar).

———. 2007. “‘Endogenous Money: Structuralist and Horizontalist’.” In.: Levy Economics Institute, The, Economics Working Paper Archive.

Wray, Larry Randall. 1989. ‘The Endogenous Theory of Money’, Washington University.