Very rarely do I review a book and find that the best way to convey its significance is to quote, verbatim, its first four paragraphs:

In 2020, during the darkest hours of the global coronavirus pandemic, the US government spent $3 trillion to help rescue the country’s – and, to some extent, the world’s – economy. This infusion of cash increased US government debt and thus reduced US government wealth by almost the entirety of that frighteningly large amount – the largest drop in US government wealth since the nation’s founding. Surely something this unfavorable to the government’s ‘balance sheet’ would have broad, adverse financial consequences.

So what happened to household wealth during that same year? It rose. And it improved by not just the $3 trillion injected into the economy by the government but by a whopping $14.5 trillion, the largest recorded increase in household wealth in history. As a whole, the wealth of the country – its households, businesses, and the government added together – increased by $11 trillion, so this improvement in wealth was contained largely to households.

How and why did such an extraordinary increase occur?

To understand this paradox, we need to seek answers to some of the most fundamental questions in economics: What is money? What is debt? What brings about increases in wealth? Often the most basic questions can be the most challenging to answer. They appear deceptively simple but they are complex and vitally important.” (Vague 2023, p. 1)

What follows is a magisterial analysis of the role of debt in economics, working from detailed data on each of the world’s major economies. The key focus is, as the title declares, the paradoxical role of debt in a capitalist economy. Debt is both a pre-requisite for economic growth, and a cause of economic crises as well.

“the 2008 financial crisis was no black swan or storm of the century phenomenon; instead, it would have been easy to spot, and might have been foretold years, not months, in advance, if analysts had been looking in the right direction and at the right things. Like most financial calamities, the 2008 crisis was born from the unbridled growth in private sector debt – a key trend that is straightforward to track.” (Vague 2023, p. 222)

And yet it is ignored by mainstream economics, leaving its analysis to a band of contrarians including me (Keen 1995), Hyman Minsky (Minsky 1982), whose “Financial Instability Hypothesis” inspired me, Irving Fisher (Fisher 1933), whose “Debt Deflation Theory of Great Depressions” inspired him, Michael Hudson (Hudson 2018) and the late David Graeber (Graeber 2011), who track the history of debt, Richard Werner (Werner 2016), who explains the mechanisms by which debt creates money, and now Richard Vague (Vague 2019, 2023), who covers the empirics of private and public debt in great and fascinating detail.

“A lending boom is optimism on steroids… Euphoria is the hardest habit to quit… Lending and debt are the agents and catalysts of that euphoric delusion. To seek to explain booms solely through impersonal, technical factors is to miss the fact that economics is a behavioral and not a physical science. It is to miss the essence of financial crises.” (Vague 2023, p. 188)

I often feel that the struggle against Neoclassical economics is like the struggle by believers in the Heliocentric model of the solar system against the then dominant Geocentric model of Aristotle and Ptolemy. Copernicus, Brahe, Kepler, Galileo, and finally Newton, were the pivotal fighters for truth in that struggle. I’m not putting any of us on the same pedestal as those critical contributors to the triumph of science over religion, but my mind often wanders to the personal parallels: whose contributions to realism on the monetary nature of capitalism are most akin to the astronomical contributions of those giants?

“In the lead-up to the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, the US accumulated a gargantuan mountain of new mortgage debt, totaling $5 trillion. This debt was so large it was practically impossible to miss – except that most economists did miss it entirely, and therefore failed to predict the financial crisis.” (Vague 2023, p. 58)

Fisher was our Copernicus, first putting forward the theory that “over-indebtedness to start with and deflation following soon after” are the key factor in causing Great Depressions”. Minsky was our Kepler, working out the elliptical ways in which debt drove economics. Perhaps, by inventing Minsky—which I regard as the monetary equivalent of Galileo’s telescope—I have some parallels with Galileo. But there is no doubt about the astronomical doppelganger for Richard Vague: it is Tycho Brahe.

“Still another objection is that this is just one more example of government trying to pick winners and losers, and only the wisdom of markets can do that. Well, in 2007, the market was picking no-down-payment mortgage loans as winners and how did that work out?” (Vague 2023, p. 226)

Tycho’s meticulous observations of the motions of the planets and stars provided the rock-solid foundations on which the Heliocentric model was constructed. This is the realm in which Vague excels. This book, and the website that supports it, does for the credit-based model of capitalism what Tycho’s measurements did for the Heliocentric model—a model without which we would still be an Earthbound species, rather than one with the potential to reach for the stars.

“Based on these ratios, debt is a peripheral issue to the top 10 percent of US households but a monumental issue to many in the bottom 60 percent… champion the trickle-down theory of economics are correct – except for one detail: it is debt that has been trickling down, not wealth.” (Vague 2023, pp. 70-72)

The Paradox of Debt: A new path to prosperity without crisis provides that data in an extremely accessible and entertaining form. It’s not easy to write about empirical facts embodied in tables and graphs, and make the prose engaging. Vague does it with ease.

“In the early 1980s, many economists made dire predictions about the likely consequences of high levels of government debt. The warned that it would constrain spending, crowd out lending and investment, lead to higher interest rates and inflation, and seriously encumber the country. At the time, inflation had reached 14 percent and interest rates were close to 20 percent.

Since then, government debt has exploded and so we have had ample opportunity to put these predictions to the test. As it turns out, over this time span interest rates have generally plummeted, not risen; investment has remained high, not been constrained; and household net worth has risen, not sunk.” (Vague 2023, p. 55)

I am in some ways too close to this topic myself—and too close to the author, who is not merely a friend, but also one of my favorite people—to write a detailed commentary and critique here. What I can say is that reading Vague is much easier than reading Keen, and provides insights that I don’t, through the wealth of data Richard has assembled with his research group—which he has, funnily enough, named after Tycho Brahe.

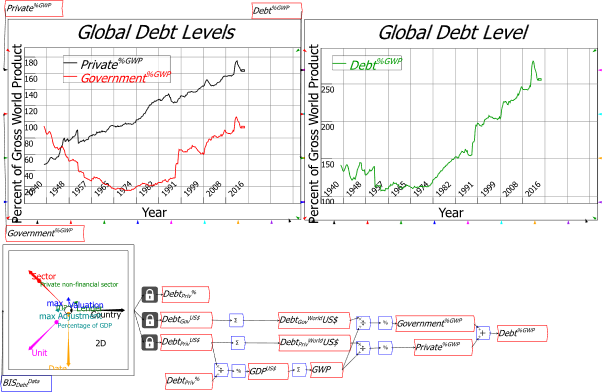

Figure 1: Global debt levels from the BIS, with the analysis done in my new program Ravel

“In particular, the growth that comes from government spending could come instead from a non-debt-based source. All it takes is for the Treasury to sell a non-interest-bearing instrument with no maturity to the Federal Reserve… Let’s call this instrument perpetual money. It may well be that a balance between debt-based money and perpetual money is a healthier and more technically sound way of managing monetary policy.” (Vague 2023: , p. 256)

Though there are many aspects of Vague’s analysis that are consistent with other contrarian theories, Richard is not beholden to any doctrines, and frequently makes observations that challenge other contrarians. For instance, he regards a trade as a negative, which contradicts an aspect of Modern Monetary Theory that I also criticise. He worries about aggregate debt—public as well as private—whereas other contrarians, me included, tend to see government debt as benign (the opposite of the Neoclassical argument). Like me, he argues for a debt jubilee, though with quite a different structure to my “Modern Debt Jubilee”.

The ratio of debt to income in economies almost always rises, with profound consequences, both good and bad.

• Money is itself created by debt.

• New money, and therefore new debt, is required for economic growth.

• Rising total debt brings an increase in household and national wealth or capital. Most wealth is only possible if other people or entities have debt. As wealth grows, so too must debt.

• At the same time, debt growth brings greater inequality, in part because middle- to lower-income households carry a disproportionate relative share of household debt burden. In fact, in economic systems based on debt – which is the world as it operates now – rising inequality is inevitable, absent some significant countervailing change such as a major change in a nation’s tax policy.

• A current account and trade deficit contributes to private sector debt burdens.

• The overall increase in debt, especially private debt, eventually slows economic growth and can bring economic calamity. (Vague 2023, p. 7)

This makes his case worthy of attention from other contrarians, as well as politicians, the general public, and the investment community. He even spices up the book with predictions, based on his careful attention to the data, which financial analysts may find both surprising and potentially rewarding.

“Any among these turns of events would likely force Germany to make some stark economic choices. Surely it would – and, given the outlook for China’s GDP growth, I’m tempted to say it will – suffer a contraction, unless the government quickly encourages large increases in private sector spending, funded by increased business and household debt, or, alternatively, enacts large increases in government spending.” (Vague 2023, p. 115)

I strongly recommend this book (the sale proceeds from which go to charity) to my own readers, and if you haven’t heard of Richard Vague before, read this excellent and entertaining profile, from the days prior to 2020 when he was considering running for President: Richard Vague May Be the Most Revolutionary Thinker in Philly (phillymag.com).

And yes, in case you’re wondering, we are considering writing a book together. The extent to which our approaches to economics complement each other is matched only by the novelty of our contradictory names.

Click here to purchase The Paradox Of Debt

Fisher, Irving. 1933. ‘The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions’, Econometrica, 1: 337-57.

Graeber, David. 2011. Debt: The First 5,000 Years (Melville House: New York).

Hudson, Michael. 2018. …and forgive them their debts: Lending, Foreclosure and Redemption From Bronze Age Finance to the Jubilee Year (Islet: New York).

Keen, Steve. 1995. ‘Finance and Economic Breakdown: Modeling Minsky’s ‘Financial Instability Hypothesis.”, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 17: 607-35.

Minsky, Hyman P. 1982. Can “it” happen again? : essays on instability and finance (M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, N.Y.).

Vague, Richard. 2019. A Brief History of Doom: Two Hundred Years of Financial Crises (University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia).

———. 2023. The Paradox of Debt: A new path to prosperity without crisis (Forum: London).

Werner, Richard A. 2016. ‘A lost century in economics: Three theories of banking and the conclusive evidence’, International Review of Financial Analysis, 46: 361-79.